Our theme this month is Artist’s books, but as usual, our writers talk about lots of different subjects so here is a good mix of our latest pieces as well as a few about out latest theme…

Artists’ books are generally not what you expect them to be, they are something much more creative and art objects in their own right.

However, an artist’s book does not begin or end in its own materiality: it can expand, become other forms, and reassemble itself. An artist’s book can be the size of a matchbox or occupy a very large space. There is no fixed dimensionality, there are no patterns, and there is no one who can tell us how to fabricate it.

An artist’s book may or may not look like a book. It is not enough to name it as such. There must be a secret pact, a game between the reader and the artifact so that the latter becomes a book

Artist name Elspeth Penfold

Website

http://www.elspeth-billie-penfold.com/

Social media links

Facebook: Thread and Word

Insta: @elspeth_billie_penfold

https://linktr.ee/ThreadandWord

Artist Statement

Elspeth Penfold (Thread and Word) is a Bolivian/Argentinian multidisciplinary artist who has lived and worked in the UK since the 1970s. Elspeth has a passion for poetry and a wealth of experience as an artist working with weaving, walking, and writing. Her spinning and knotting work draws on the Incan history and technique of ‘Quipu’ (knotwork), an ancient and nuanced form of communication used by indigenous communities.

Elspeth’s commissions include Reclaiming the Narrative, at Turner Contemporary; Intertidal Calligraphy with Walk Create and The Museum of London Archeology; Port at Art Walk Porty, Edinburgh; and, Walking with Ghosts in Folkestone, a live art commission with the Imperial War Museum and The University of Kent.

As an artist in residence with East Kent Mencap, Elspeth is currently working on Coasts in Mind. This is an intergenerational project with The Museum of London Archeology, supported by the National Heritage Lottery. The project empowers local communities to contribute to environmental policy through gathering oral histories of coastal change.

Name of the work

Intertidal Calligraphy

How many issues are there & has it been shown in public/exhibited?

100

It has been shown at The Gathering with Walk create funded by the arts and Humanities Research council and a number of participating institutions . https://walkcreate.gla.ac.uk/walkcreate-gathering/

More recently at the London Spanish Book and Zine fair https://www.latundra.com/london-spanish-book-zine-fair-2023-full-programme/

Why was your artist's book created?

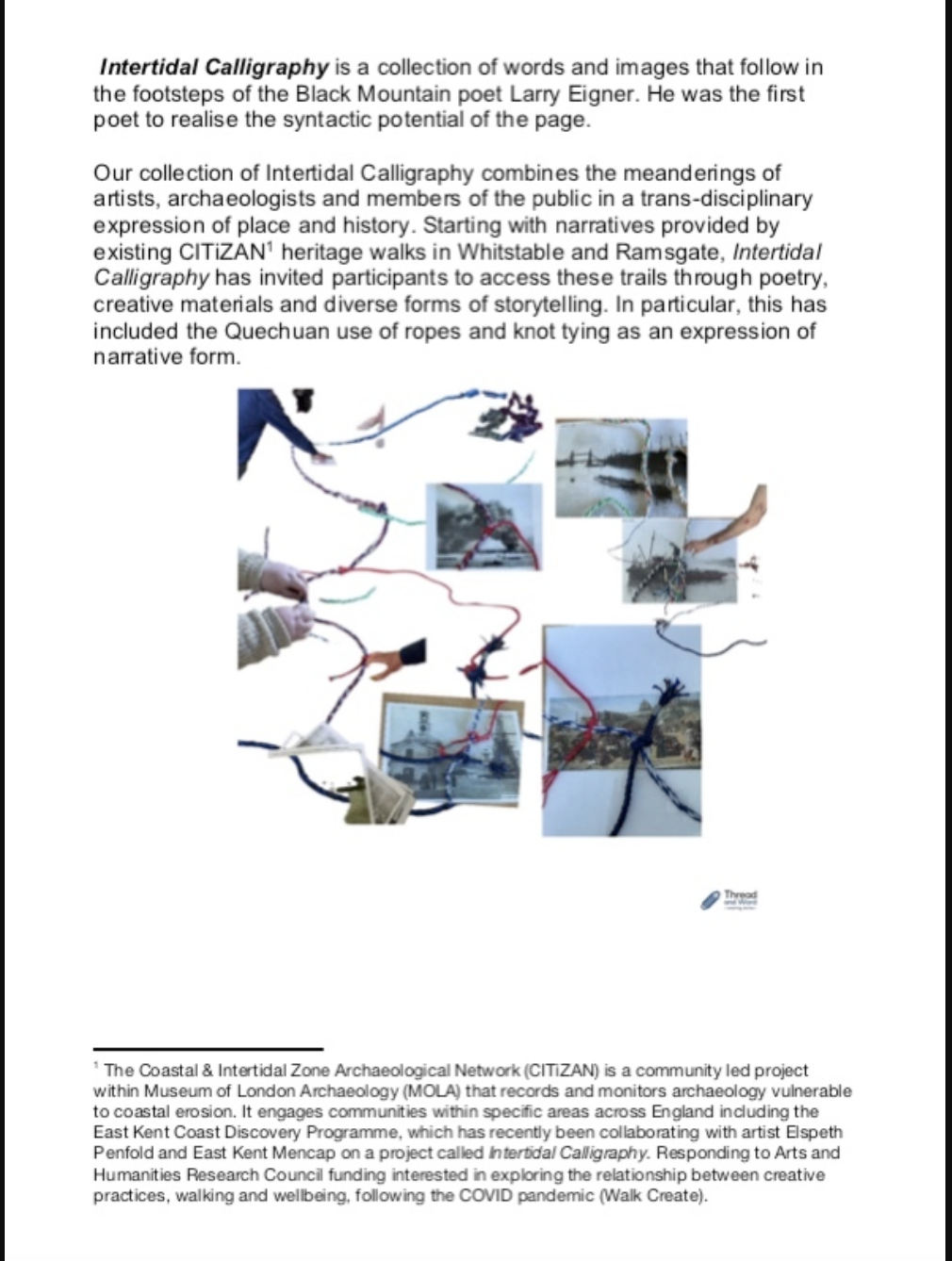

Our collection of Intertidal Calligraphy combines the meanderings of artists , archaeologists and members of the public in a trans-disciplinary expression of place and history . It was as co-created with members from east kent mencap who are adults with a learning disability. It connects the local environment with social inclusivity. The Zine starts with narratives provided by an existing heritage walk by CTIZAN in Whitstable and Ramsgate . Intertidal Calligraphy invited participants to access these trails through poetry, creative materials and diverse forms of storytelling. In particular, this has included the Quechuan use of ropes and knot tying as an expression of narrative form.

>>>>>>>>>>>><<<<<<<<<<<<<<

Artist name -Thomas lisle

Website -www.thomaslisle.com

Social media links -https://www.instagram.com/thomaslisle99/

www.linkedin.com/in/thomas-lisle-83539b71

Bio

Thomas Lisle is a British artist based in London. He works in digital 3D animation, painting, digital images, and installations. His work references, psychology, science fiction, and the environment through the medium of digital 3D paint/sculptures, he has been making video and moving image art since 1983.

Lisle studied at Jacob Kramer College of Art in Leeds, then at the University of Reading (Fine Art Department). His work has been featured in exhibitions and screenings in the UK and internationally since the mid-1980s. He has artworks in the collections of Tate Modern and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. His recent animations have featured in festivals including Matadac Spain, Pixel Fest Moscow, Lumen Prize touring exhibition, Leeds City Hall, The Psychedelic Film and Music Festival NY, and SFE.TV Art cable station in Germany, and FILE Brazil.

Lisle was one of the first artists to investigate glitch video in the 1980s and 1990s - notable projects include the Arts Council-funded Fish out of Water, I, Claudius, and Portrait of a Francois. Lisle used Glitch TV images which had a reference to painting and projected them through moving projectors.

Lisle started developing his digital artworks in the late 1990s and made a number of digital 3D animations which were shown extensively Internationally. His digital work started working with cubes, planes and particle systems and evolved into a more painterly adaptation in digital 3D.

Digital art, time, painting, sculpture, and consciousness

Intro

The art world seems to be in a moment of change; suddenly, digital is relevant to more people. As an artist who has embraced electronic and digital art since 1981, I think it's important to understand in more depth digital technology and its implications and its relationship to art. My aim is to give those who do not have 40-odd years of experience a deeper insight into the technology, ideas, and practice of digital art from the perspective of my artistic output.

I started making glitch video art in 1981 as a process to make abstract painterly images. I eventually came to the conclusion that it's really inadequate; it's like outsourcing the creative aspect, the making of the abstraction to some random process, and it doesn't offer real control, sometimes, it throws up something interesting, but at what price? I described glitch art in 1986 as a deconstruction. A glitch is a technical malfunction; it's impersonal. Glitch art seems ‘classical post-modernist’ along with AI and generative art and seems rooted in the art thinking and practice of the last century.

A glitch is like throwing a bucket of paint over your shoulder, occasionally, something new and interesting might appear. But the process of thinking about the artwork and the journey of discovery, with tools you can finitely control, is far more meaningful, related to our consciousness, and produces results that can be built upon and developed, what I would call a metamodern approach to art. AI art can't even be copyrighted in the US as of this year.

As an artist, I'm interested in abstraction, colour, visual languages, and psychology. Figurative abstraction, above all, seems to me to be the most human mode of expression. Figurative and Non-figurative abstraction, when time-based, brings a new dimension to art and allows abstract forms to take on a narrative, it is a paint form/sculpture that's saying something through its time-based transformation/journey. Time gives new meaning to manually made marks.

If you were to ask me what digital medium offered artists the scope to produce any form, any painting, 'time-based meta-plasticity,' i.e. the art of the future, I would say without a moment of doubt it's 3D animation software.

The new possibilities of this technology are multiple and profound. Painting becomes painted sculpture and time-based painted sculpture. These are really fundamental shifts in the painting/sculpting universe. The integration of psychology into my work seems to me fundamentally a meta-modernist approach to art. In terms of subject matter, psychology is, after all, the study of consciousness. And the hand-to-eye relationship in painting is the key to visualising consciousness.

Nearly all artists using digital 3D are not using any painting; they are modeling objects (or using models from the net) or using particle systems. Some artists abstract their models by manipulating and animating the points that form the model. The particle systems are driven by the maths of random noise fields. These artworks are not paintings, and there is no hand that has drawn/painted anything in them. They may have some visual relationship to painting, but that's where the analogy ends.

How do contemporary painters transition from the material to the virtual and time-based? From my experience, it is by finding ways to simulate paint. I discovered that what flows out of a virtual digital paintbrush can offer infinite possibilities.

Look at Glitch art: in the 1990s, it was difficult to get the technology and difficult to make. Today, every art student has access to the Adobe Creative suite, where they can use hundreds of templates with After Effects to make Glitch effects. Now, it's mainstream. What I'm doing today will be mainstream in 20 years as soon as Adobe makes an app that comes free to every art and design student.

It is essential to understand what digital artists are doing to be able to evaluate the art. It's difficult to evaluate something if you don't know anything about it.

The number one key factor I apply to all digital art is, "Is this visual effect? I'm looking at something unique, something handcrafted, and to what extent is it handcrafted? Is anything actually modeled or painted by someone?"

When you think about, say, Albert Ohlen talking about his painting, where he describes the process as being all on the canvas, there's nothing hidden. I would say the same is true for most of digital art, but that's because I know the capabilities extremely well, having been working in this field for 40 years. It's just not as simple as pencils and paint, which everyone has some experience in. The definition of painting is that it can only be made by using your eyes and hands with or without a brush. Typing/generating code to create a square is not painting! Applying a filter to some video footage, algorithmically generating shapes, and scanning an object in 3D are all not paintings. If there isn't any actual painting involved, then it's not a painting.

Human consciousness or AI

What appeals to me about painting/sculpture is and always has been the consciousness behind the artwork; it's impossible for AI or an algorithm or a vast database of information to ever know what it is to be human. It's the originality, poetry or beauty or chaos, craftsmanship, and the emotional, transcendent, humbling impact that humans bring to art that matters. Art is one of the most important ways to understand the world, people, and ourselves.

There seem to be universal physiological and philosophical structures, such as 'existence', 'how do I live my life', and 'concepts of consciousness'. Art needs to explore the personal and compassionate to be meaningful.

Is it possible for AI to ever know what it is to be human? Joseph Weizenbaum first pointed this out in the 1960s when he invented the first chatbot, that AI can't make judgments and has no values but that they can only calculate. His AI chatbot mimicked a psychotherapist, and people believed it.

People thought the AI chatbot was a human or, in other words, had intelligence and compassion. The reason it's relevant today is that psychological transference is taking place in the art world, believing something that is inherently untrue can only cause issues in society and on a personal level. Anyone who thought a computer cared about you would be totally deluded and is being manipulated.

Digital art made by AI systems is basically fooling us into thinking that what we are looking at is man-made and has human attributes. Do you want to hear, read, or see something that talks about the human experience from a human or some AI program that scrapes the internet and draws conclusions based on things it can never understand?

Only human consciousness and human intellect seem relevant to me.

I think generative art, which produces thousands of random variations on a theme, is outsourcing the creative process too, it's impersonal and unsympathetic. I will always remember in the 1980’s, I showed a hard-edge painter how I made a square and a few circles on a computer. “This makes a mockery of hard-edge painting,” he shouted. Really good hard-edge painting involves great composition, colour theory, and the commitment to realise the work by hand in paint it is totally different.

The paintings of contemporary painters are not random and are rooted in the tradition of abstract art that spans over a hundred years. If you don't understand the principles of form, visual rhythms, and colour, and you don't know anything about art history and how contemporary art evolved, then it shows in the artwork, as does art made randomly.

Time-based abstraction

Time implies that there is a narrative, a progression, a process, a story, or all combined. Painting up until this time had evoked movement, been called capturing movement, even called dynamic, but it was all static. Digital painting does away with the tiresome need to paint every frame by utilising procedural technologies. The funny thing about 3D painting is that it's a sculpture! And as soon as you animate it, it is telling a story, it's got a history. In my time-based abstract paintings, each element moves, transforms, deforms, evolves, devolves with a purpose and tells a story, has a narrative. It is a process that I equate with mental processes in the abstract.

The majority of contemporary digital art is time-based, and this is a fundamental shift in thinking and working practice for artists. I think art needs to reflect internal processes, ideas, and concepts, internal reality abstracted to make it easier to understand, and, of course, that reality is in constant flux; it is dynamic and multilayered.

Reality is not flat. You can see Picasso taking a real interest in 3-D abstraction, especially in the 1930s and 1940s, even 3D tubular lines. Picasso was pre-empting the digital possibilities of today. Painting/sculpture needs to evolve. Time-based 3D paint is clearly the next step in its evolution. Hollywood drove 3D animation systems to evolve to make impossible things look realistic and be time-based, from explosions to aliens. There are so many different things in the real and imaginary worlds that the software the engineers built became totally modular and interconnected so that it could meet the needs of the industry to visualise anything that anyone thought of. They expose and allow accurate manipulation at the pixel and voxel level, the atomic level of digital images.

When you make software that can make anything visually, you have tools that contemporary artists can make use of to make contemporary art.

We are probably at the stage where we have the tools to reproduce oil paintings digitally; the only thing holding us back is computing power, and that seems to be on a never-ending upward path.

Poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity. Audre Lorde

Understanding ourselves, our motives, and our conditioning seem to me to be the keys to unlocking a better society, better art, better environment, and better thinking.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>><<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

Artist name Siobhan Wall

Website

Social media links

@siobhan_drawings ( Instagram)

Artist Statement

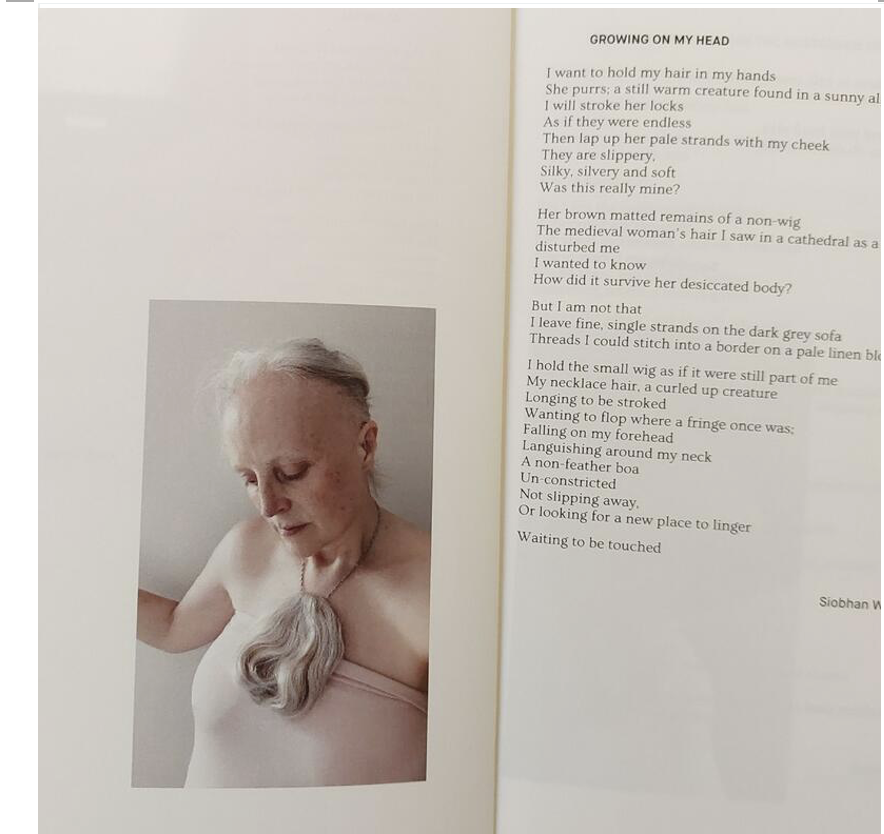

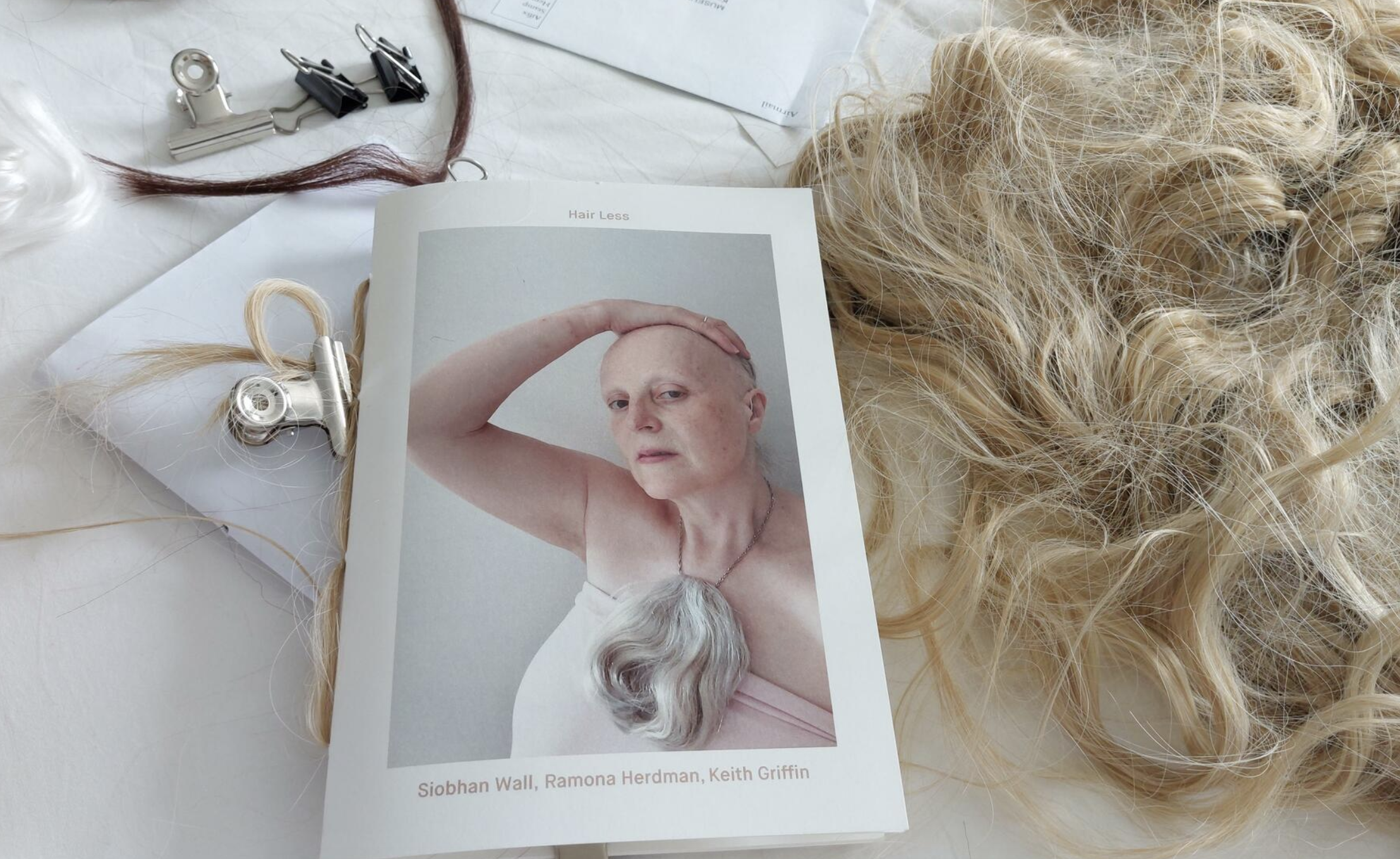

Inspired by feminist art practice and writing, my work engages with ideas around the imperfect body. I use whatever medium is ideal to address the indignities and inconveniences of being disabled. I am living with MS and am partially deaf. I mainly draw and write but also use photography to explore what it means to live in an unreliable body. My most recent work took the form of a book - the binding was sewn with synthetic grey hair.

Name of the work

Hair Less

How many issues are there & has it been shown in public/exhibited?

100 copies printed. Not shown so far but a poetry reading is planned at the Alopecia Society meeting in Sheffield on 16th October 2023.

Why was your artist's book created?

I have hair loss as a side effect of taking medication for multiple sclerosis I wanted to make female baldness beautiful as well as include poems about what it feels like to be bald. I wanted to connect with both bald and non-bald readers.

>>>>>>>>>>>>><<<<<<<<<<<<<

Artist name

Daniele Marzeddu

Contact email

daniele@danielemarzeddu.com

Website

www.danielemarzeddu.com

Social media links

https://www.instagram.com/danielemarzeddu

Artist statement

I first read Lawrence’s "Sea and Sardinia" when I was fifteen. At the time, I was a very disoriented adolescent with a passion for music and visual art. I found literature generally interesting, but like many other schoolmates, I felt it was an obligation, a burden imposed on us by our archaic grammar school.

My aunt Daniela gave me a copy of the book for my birthday, and it was during that following year - at the warm dawn in September - that my mum and dad decided to head towards Mandas station to get aboard the train to Sorgono. Despite being struck by the creative usage of language whilst observing the landscape from the train window, I found it tricky at the time to delve into the Lawrentian vision of the world. Many years were to pass before I could grasp the concept of “spirit of place”.

Still resounding loud in my mind is Jack Nicholson, acting as George Hanson in Easy Rider (USA, 1968) saying: “Here’s the first of the day, fellas. To ol’ D.H. Lawrence”. He sips avidly at his first taste of bourbon/freedom after his release from jail. That film was set on a different continent and in a different time, but accordingly, both the director Dennis Hopper and Nicholson were well-versed in Lawrence’s poetics. It is said that they spent their free time with some Native Americans who lived near Kiowa Ranch (today the “D.H. Lawrence Ranch”) at Taos in New Mexico, and used to have a siesta by the grave of the writer the day before shooting that scene. Inspired by these stories, I tried to get into a similar sensorial experience by visiting some of the locations, such as Sardinia, that Lawrence and Frieda visited in 1921.

There have been countless reasons that led me to embark on this challenging project. Through my photographs, I aimed at creating “written” images of places and people that inspired my interest. Amazingly enough, I found a certain correspondence with Lawrence’s observations, though 100 years later. As we know, Lawrence was determined to produce a fully illustrated book (see Long’s essays, p. 79), so I embarked on a trip around Sardinia and Sicily. By using one of my old film cameras I followed in his steps from the coastal Sicilian town of Taormina all the way up to Palermo, and then boarded a ferry to my ancestors’ land, Sardinia. As anticipated by Ceramella in his introductory essay (p. 1), stylistically I opted for black and white pictures since I felt it was a more appropriate means of expression: I wished to create a transitional timeline connecting the two islands and comparing their contemporary status of insularity.

A century of evolution and technology seems to have brought a positive impact to some remote areas of both Sicily and Sardinia. Even so, I could notice – especially all along the Trinacria (the symbol of Sicily) – an authentic and perhaps morbid sense of belonging to their regions. For instance, in the historical borough of Borgo Vecchio in Palermo, most of the local folks acknowledged their obstinacy on not even going for a stroll to the city centre. I highly sensed how their attitude reflects a deep sense of local community that precedes almost anything: the town, the nation, the world. In fact, a space such as a square can be their own world.

hours in the middle of their own microcosm, Piazza Ximenes. Despite being spotted taking sneakily images of a loan shark candidly working out in the open, I ended up speaking in Sicilian with them, freezing moments of pure “Palermitaness”.

There is no doubt that, amongst other reasons, the continuous desire of building cultural bridges between Britain and the two largest islands of the Mediterranean Sea convinced me and my partner Vicki to experience such an adventurous journey.

We still are nani sulle spalle dei Giganti (“dwarves perching on the Giants’ shoulders”), but literature, once again, has created new cross-arts forms a century on.

Name of the work

Via D.H. Lawrence

How many issues are there & has it been shown in public/exhibited?

It hasn't been published yet.

Why was your artist's book created?

My aim was to create photographs that D. H. Lawrence himself really wanted to insert in his own travel book.

He responded to the advent of photography like many other writers of his time. It is no wonder, then, that he stubbornly considered the possibility of using photographs to illustrate Sea and Sardinia. On his return from his ten-day trip with Frieda around Sardinia (4–13 January 1921), he wrote to Mountsier, his American agent: ‘I am still doing Sardinia. It will make a little book. Have written to Cagliari for photographs’ (L3, 662). About three weeks later, on 22 February, he returned to Mountsier saying: ‘I have finished the “Diary of a Trip to Sardinia.” […] I hope to send you the MS. With photographs complete within a month’s time’ (L3, 667). After a week, he complained that he was ‘awaiting typescript of “A Trip to Sardinia”: also, most anxiously, a reply from Cagliari about photographs for the same’ (L3, 375). Although he received part of the MS in a few days, he was still very nervous because there was no sign of the photos. On 22 March, a determined Lawrence wrote to Mountsier: ‘I still haven’t managed to get Sardinia photographs; only Sicily. But I don’t give up’ (L3, 688). Another week passed and he confirmed: ‘am still struggling to get photographs, and I hope to succeed’ (L3, 695-6). After two days, at the end of March, on suggesting some alternative titles to the provisional ‘Diary of a Trip to Sardinia,’ Lawrence included some pictures of Sicily. Then, he informed Mountsier that he was thinking of some new possible titles for the book: ‘[…] Sardinia Films or Films of Sicily and Sardinia […]’ (L3, 696). Indeed, this idea is confirmed in a letter to Curtis Brown, Lawrence’s agent for England:

I am still struggling for photographs of Sardinia itself. – and a friend of mine, Jan Juta, is just going to Sardinia to paint suitable illustrations for the book, in flat colour. […] The title for Sardinia book Mountsier objected to. I suggested others: Sardinia Films for example –’ (L3, 705)

>>>>>>>>>>>>>><<<<<<<<<<<<<<