Accumulation: Between Archive and Excess

Accumulation has long been a driving force in art, literature, and culture. To accumulate is to gather, layer, and preserve, but also to risk being overwhelmed.

Artists and writers have returned to this theme again and again, fascinated by the way repetition and excess can both illuminate and obscure meaning.

In art history, accumulation has been a method of critique and creation.

Arman, one of the key figures of Nouveau Réalisme, created his “accumulations” in the 1960s by encasing heaps of everyday objects, gas masks, clocks, toys, in resin or plexiglass, transforming consumer detritus into monuments of modern life.

Andy Warhol’s silkscreens repeated images of Marilyn Monroe or Campbell’s soup cans until the aura of the original dissolved into commodity spectacle.

Yayoi Kusama’s obsessive dot patterns and installations, endlessly repeated, dissolve individuality into infinite excess.

Similarly, Hanne Darboven’s monumental wall works, made of calendars and handwritten sequences, embody time itself as a relentless accumulation of marks.

In literature, accumulation emerges as a stylistic technique: Gertrude Stein’s loops of repetition, James Joyce’s sprawling catalogues, and John Ashbery’s proliferating associations turn language into a living accumulation of sound, rhythm, and thought.

More recently, writers like Anne Carson and Ben Lerner have explored the layering of fragments, voices, and references as a form of accumulation that resists neat closure.

Yet accumulation also has a darker side. The obsessive drive to collect or preserve can tip into pathology.

Compulsive hoarding, now recognised as a psychological condition, exemplifies how the act of saving, originally protective or sentimental, can spiral into overwhelming excess, threatening the very space of life.

Artists such as Christian Boltanski and Song Dong (Waste Not, 2005) have staged this tension, presenting piles of clothes, objects, or personal effects as haunting monuments to memory, survival, and compulsion.

Accumulation also mirrors the digital age: endless feeds, data storage, image hoards, and archives without limit. Contemporary artists working online often grapple with the impossibility of curating or filtering the flood of material.

Accumulation becomes both the condition of creation and its critique.

This month we had a large collection of work submitted from our readers.

Our Resident Writers -

Museums of meaning - Michaela Hall

For some the idea of collecting and storing objects is comfort, for others it's chaos. We all have different relationships with gathering, some of us are sentimental and some of us not so much - from everyday objects to the most sacred of pieces, we all see value in different things and have our own approach to what we keep and archive. In other words, what we find meaning in. This is something that is often explored through creative practice with artists leaning on this exploration to show us into their world and their own approach to this.

For some, such as Canadian artist Sara Cwynar, these objects become mediums for creating works in their own right. In her 'Accidental Archives' project, the artist used her own collections of saved and worthy objects to create colour themed collections that are expertly curated compositions. They seem to be a collection of unlikely objects, yet at the same are harmonious and create their own narrative, very much a nod to the artist's own narrative while allowing the viewer to make their own stories up about the different 'archives' and what life these objects could have lived. From photo paper and photographs, to food, books, clothes and carrier bags - there's a bit of everything and the different colour- themed pieces offer us more questions than answers, their presence both intriguing and strange but beautiful.

Putting objects together to create new forms and meaning is something that artist Sir Anthony Douglas Cragg CBE RA is a master of, and it would seem amiss to explore objects and how we collect and work with them without a nod to him. Cragg is famous for many different approaches to his work but one to note are his early works - assemblages, that is the putting together of existing materials to create something new. They are bold and their presence is demanding for us to dig deeper and uncover all the hidden objects to make up these large-scale inviting sculptures. In 'Black and White Stack' similar to Cwynar's rainbow archives, we see a black and white curated stack of objects in two halves, and we can make out everything from pieces of wooden panel to cotton reels - it's a sea of the same colour with a mixture of extremely different objects.

What both of these artist's demonstrate is the ability to turn any object in the right hands into significance, with its own life and meaning - these artworks are museums of meaning, carefully crafted decision logs and exhibits that have something to say about their artist and their thinking, as well as what they attach meaning to and how they approach collection and the world around us.

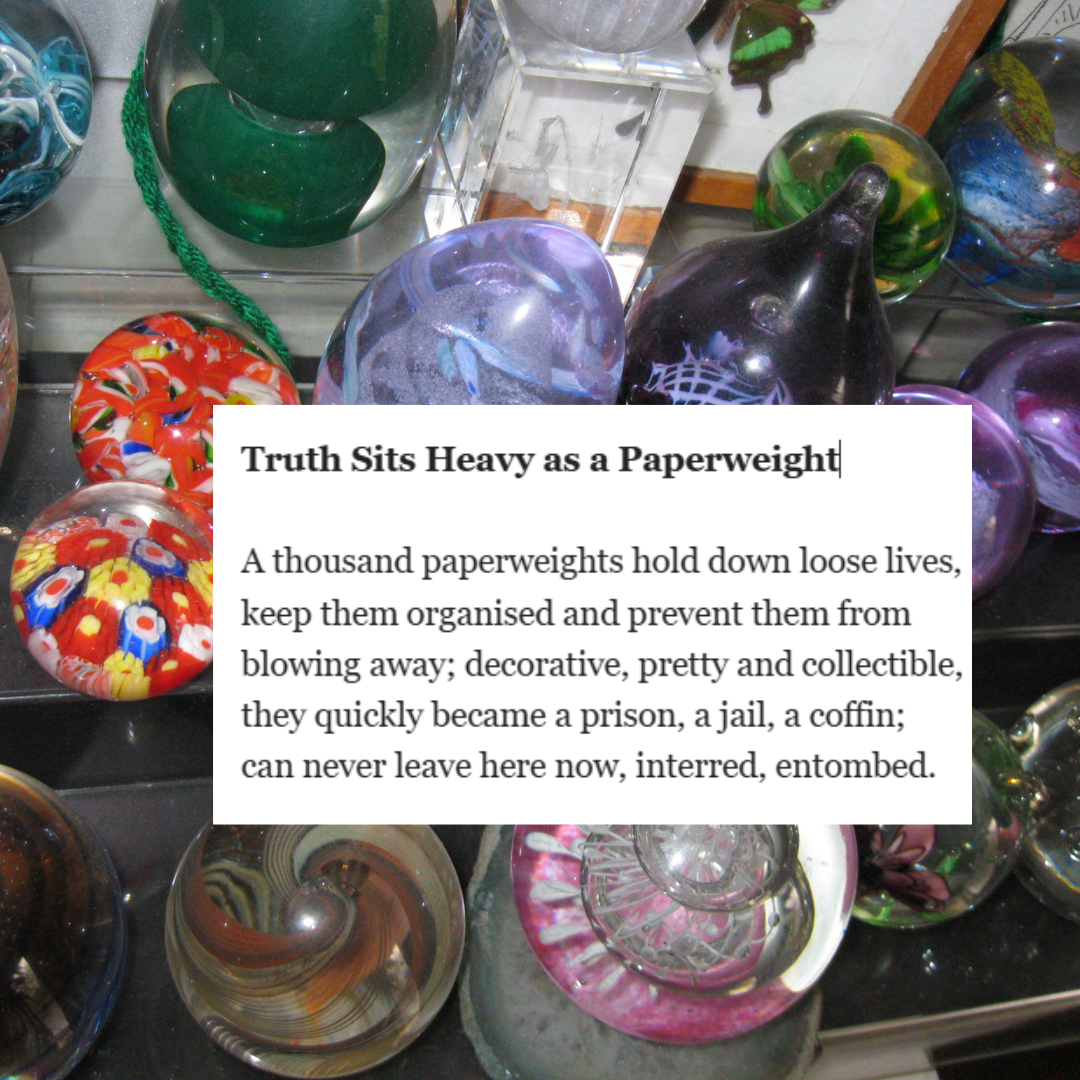

Peter Devonald

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>><<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

Our Submissions this month…

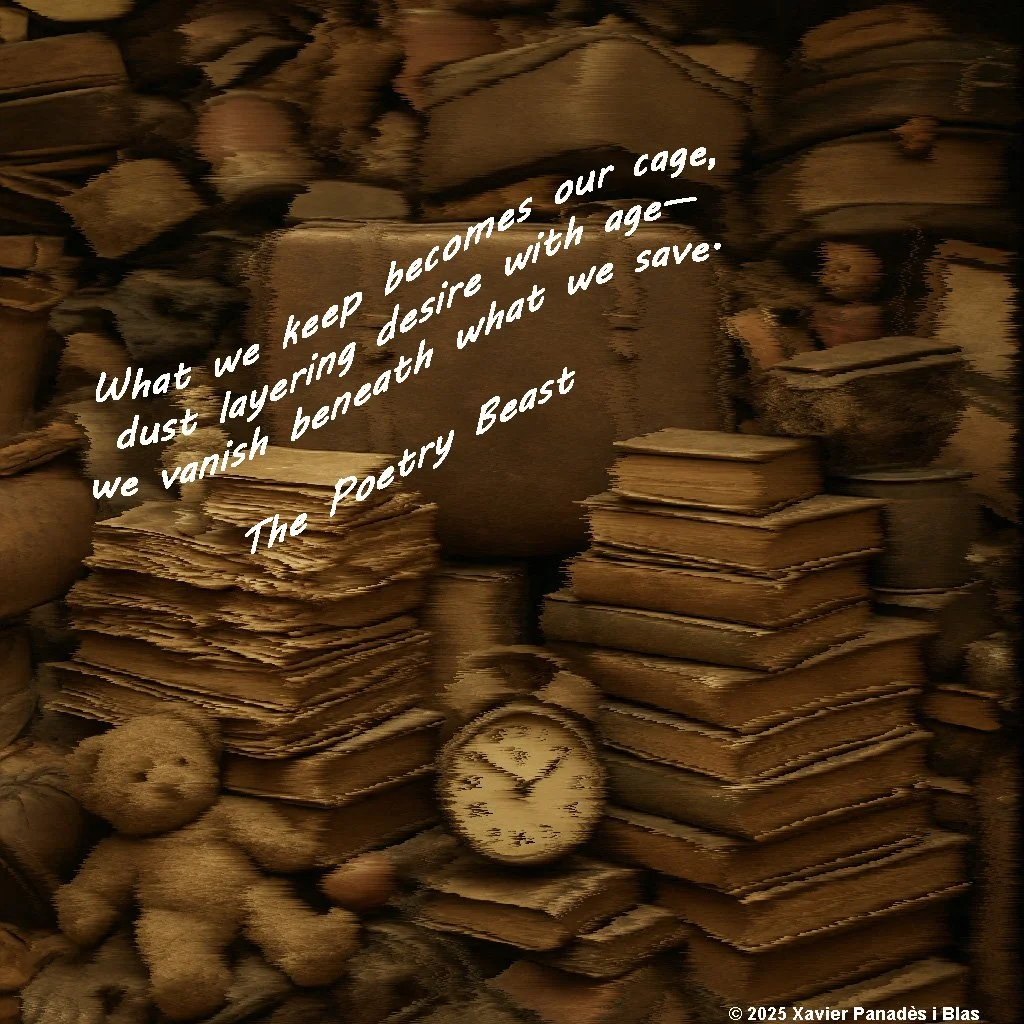

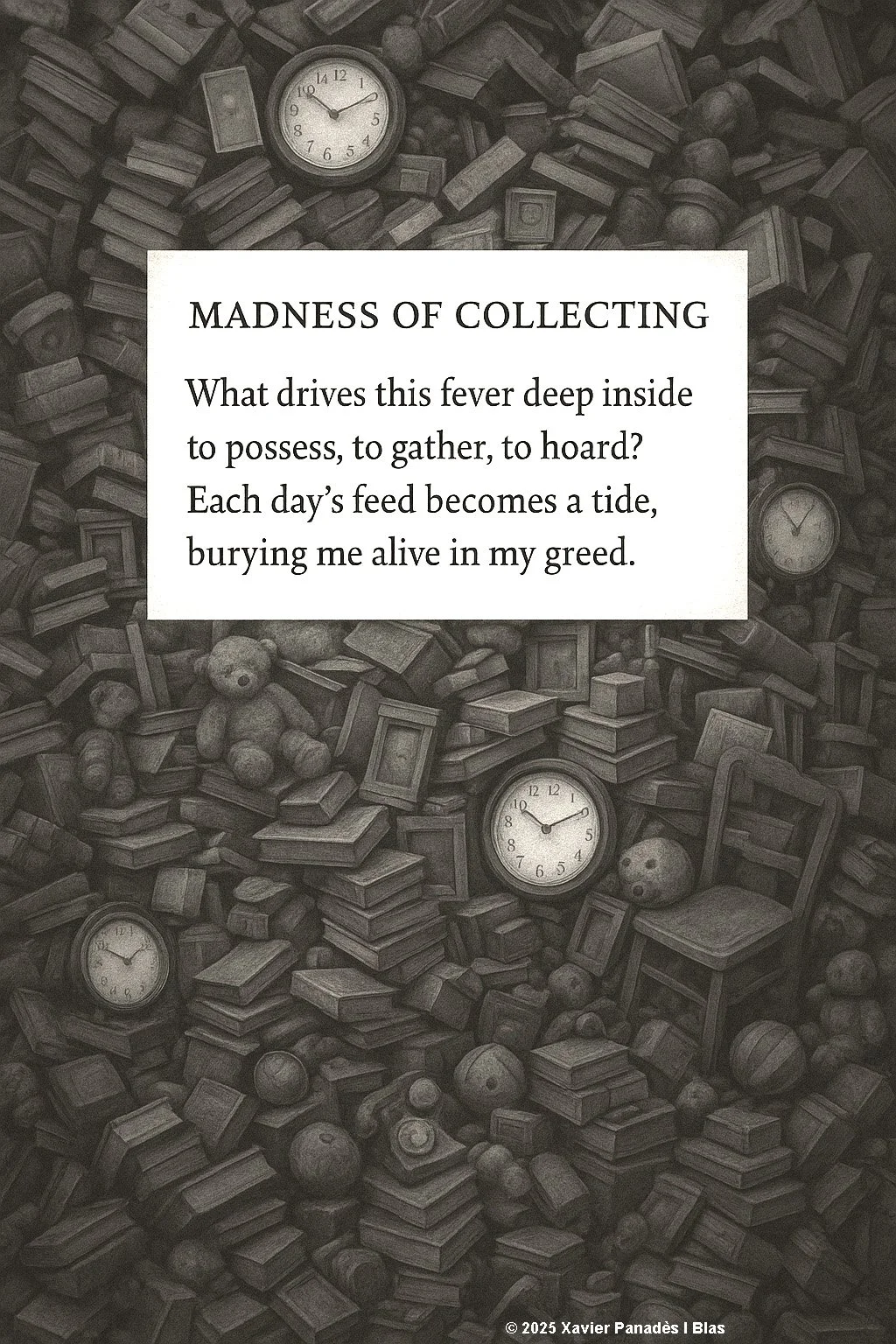

Artist name - The Poetry Beast

Social media accounts

@the_poetry_beast https://www.facebook.com/thepoetrybeast @thepoetrybeast

Website - https://thepoetrybeast.bandcamp.com/

Description

Madness of Collecting visualizes the psychological weight of accumulation. Encased within a sea of books, clocks, toys, and forgotten objects, the poem reflects on the feverish impulse to gather and possess. The grayscale palette evokes both memory and decay, turning ordinary detritus into a monument of human desire. The work meditates on the thin boundary between preservation and obsession—where the act of keeping becomes its own kind of burial.

Artist Statement — Accumulation

My work treats accumulation as a verb—an active choreography of holding, layering, and re-sounding the ordinary until it changes state. I’m drawn to the minor archives we build without meaning to: pockets and browsers, drawers that refuse to close, photo rolls that repeat the same sky until the sky becomes a chorus.

In poems, fragments, and micro-fiction, I try to make the overlooked item ring again—not to worship excess, but to listen inside it: a ticket stub as liturgy, a voice memo as inheritance, a jar as a temporary cathedral for air. Formally, I move between list, instruction, and narrative to mimic how memory actually behaves—looping, misfiling, returning at odd hours with perfect detail and missing dates—so that repetition becomes both engine and echo.

The pieces sit between archive and overload: less about romanticising the past than noticing the present tense hidden inside piles, feeds, and stacks. I’m interested in the thin seam where collecting becomes compulsion, where preservation turns to clutter, where meaning flickers between signal and noise.

Accumulation, for me, is less about owning things than about attention—how attention gathers, crowds, and arranges the world. The keepsake is simply where attention decided to sleep; the work is the moment it wakes and asks what must be kept, and what we must let go.

Accumulation 2 explores the haunting beauty of material excess. Against a backdrop of worn objects—books, clocks, toys—the poem drifts like a whisper of conscience, its words curved and ghostlike across the scene. The text evokes the spectral nature of ownership, suggesting that every item we keep holds a trace of ourselves. In this still life of clutter and decay, memory and matter intertwine, revealing how the act of collecting can transform both space and spirit.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>><<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

Artist name - Lynn White

Social media accounts

https://www.facebook.com/Lynn-White-Poetry-1603675983213077/

Website - https://lynnwhitepoetry.blogspot.com

Description

Stuff - about accumulation and shopping.

Her Collection - about memories of someone's collection and its value.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>><<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

Artist name - Janet Lees

Instagram: @janetlees2.0

Website - https://janetlees.weebly.com

Description

Poems that touch the theme of accumulation in different ways, from the collection of character facets as an individual to our collective over-consumption.

Everything’s a festival

Festival of art. Festival of words. Festival of music. Festival of dance. Festival of heart. Festival of head. Festival of belly. Festival of hands. Festival of all things cultural and civilised, with Hunter wellies, vacuum-packed summer berries, glamping pods, and proper knives and forks. Festival of festooneries, at which brassy helium balloons rub shoulders with wrinkled old blow-ups and find surprising friends in common. Separate festival of plant-dyed hand-felted bunting.

Festival of blood-sucking flowers and flesh-eating shrubs. Festival of cheese-graters, parmesan-shavers and other cheese-transmuting items. Deconstructed event comprising geographically scattered locations and random acts of noise signified by a symbol resembling a lower case i with two dots but in reality basically a festival. Festival of festivals, where festivals go to steal ideas, eye each other sideways, get hammered and fuck like rabbits (spawning yet more festivals).

Festival of towers – the tower of your dreams, your forever tower. Festival of NOW, unfolding eternally in the present moment, god help us. Festival of the realm of perpetual sunshine. Festival of diamond-hard beliefs in unbridled twilight. Festival of stealth and burning. Festival of jump. Festival of howl. Festival of scrape. Festival of teeth and fingers. Festival of the ghosts of ransacked cathedrals. Festival of chickenhearted spells to recast our immutable future. Festival of runes and roulette wheels and cracked mirrors. Festival of our broken reflections, the skittering ivory ball. Festival of the lost bets. Festival of the disappeared tusk. Festival of the nicotined waterfall of glass.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>><<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

Artist name - Matthew Steven Tett

Social media accounts

@CreativeInBoA

Description

This is a mini piece of prose - it could be described as flash fiction, or a flash observation - about the accumulation of someone's life.

There’s sanctuary in the chaos

The pile teeters, wobbles, and a crinkly, brown-edged copy of The Sun slips to the carpet. It lies there, askew. Will more fall? Will the tower stay as it is or will there be a catastrophe of tumbling newspapers?

There’s a path snaking through. There are boxes, parcels, packages, envelopes, some gaping open, some sealed neatly. There’s a harlequin of colours suggesting excitement and thrills. No matter - something else is more distracting.

A hutch with a smaller hutch on top, then a cage fit for a squeaking rodent. It’s a trio of animal homes. There are twin rabbits, Bonzo and Bonsai; guinea pigs, nameless; and red-eyed white mice, scurrying and nibbling the bars. There’s movement. Cats stalk, wide-eyed and focused, the prize so near but so far.

It’s a trove of treasures, a knick-knack shop, a jumble sale, a sight for sore eyes. But above all, it is home – sweet, heavenly home – for the owner of this place. It’s all they’ve ever wanted and for that we have no right whatsoever to judge, to criticise, for this is a comforting gathering of possessions, a crammed room full to the brim with what constitutes living.

>>>>>>>>>>><<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

Artist name - Harlan Vaughan

Social media accounts

https://www.instagram.com/i.s_rowley

Website - https://linktr.ee/i.s_rowley

https://harlanvaughantheserotinals.bandcamp.com/track/katherine-the-astonishing

Description

Accumulations of injury and intervention documented in Nottingham General Hospital case notes on Kitty Hudson (b. 1765) become entangled in systems not built to differentiate between trauma and code, and where attempts to honour the past always risk becoming implicated in procedural violence. In the ‘pile -up’ of clashing registers, where clinical diction vies with botspam, liturgical lament runs into meme-bait, this song-poem wrestles with the diminishment of the lived body through datafication, the digital image-glut and simulations of suffering and care.

[Instance: ARNOLD.STMARY

Entry Conditions Object ID:

KEY.SEXTON-83]

In her mother church

she sweeps pew and aisle

to earn her keep,

every pin and needle

put alike in her mouth.

Some traded with the housemaid

for a stick of tuffy;

some stored as sleep-aid

‘til those cruel attentions

wore back teeth to the gumline.

Process out, following

the maces, the chaplain, the architect

to Derry Mount — that slighted monument

to national fracture.

Recover again

the plate beneath the first stone:

‘Domini Nostri Pauperes.’

Smoke-smeared white horse slumped

by cauldron of stripped coffin lead —

to be communicated religiously,

ascend the vyse to trim the lights

and veil the crucified.

[Effect: Access to sub-crypt infirmary zone

beneath nave geometry

Palette: rusted blue

sepia-stained tilemap]

Black spot on pulsating arm,

static-streaked linen —

1785 rumbles from the over-way.

Black spout

ripped off thatched roofs,

thickest branches

writhen to the ground,

child flung two spear lengths high,

400 sheep drowned.

Celtic beloved forgive our

derivational trespasses

and dumped lime bikes.

Retching at leachate components

with chronic exposure

to the caustic formation,

there’s sloughing of gill tissue,

neuro-disruption.

Desire a stopping to not

avowing the incalculable zero.

Point-getting exhaustingly

in rectangular hole-churn

of say anything — all

the rage of soft pollutants.

Pavlovian bait

a must equated with

tail-flagging over

burnt umber notes

from a pyrazine cocktail.

[Audio.recurse/theyre_inside_again]

Passed another yesterday:

frame-cramped.

After twist fever,

the phthisis.

Speculator-surge gave not

a jot for the airflow

and the stockinger who tasted

not a pinch of snuff

or butter morsel.

Phlegm-stuck dilatory

before Combination Laws,

a class by themselves

living for today emptied

into earth privies and middens,

peeping out from blind-back

as the Union cries organise.

Muckwater running under thin walls.

[Cursor drift]

Clickhogs head-bobbing,

sham e-coprolalic.

Can haz cheezburger

straight to slackjaw

[Latency desync]

from Mesozoic corpse-cavern

via softbank harbour

sovereign wealth fund.

Let live me me energy sink-

stream of whetted hooks.

Auto-parasitic standard

seeks ACK/SYN amen.

Little Wang’s sawn off left hand

ground with endosperm

into hollow white flour.

Untended field and silver drain

now grey matter shrinkage

in right OFC from limbic humiliation.

Crib-biting to Jihadic drill,

sneak out another

piss-can from battlestation

Points pushed through skin.

Forceptual hold

of amnesiac debris

from masterminded quietus.

Pre-cosmic deicide challenge

grafted into her breast.

Wish for the sweet still night

felt very plainly.

[Polycount loops at LOD3–LOD6

overlapping detail shimmers]

Nimble-fingered mesh-mending

and smooth tulle pull

of the mechanised age

only adds to ruinous eye-dust.

Thymus part schirrhous

removed –

quite well.

II

Readmitted –

bolus and bath.

Bolus and bath.

A splinter comes away

near gonion.

Some pins migrate

to more distant sites;

some stuck in dressing

after breast extirpation.

No incense-scented blood

or Franciscan with three angels,

but an out-patient, Goddard,

now one-eyed,

swore to wed Kitty

even if she lost every limb.

How to beat being patched –

trust suffering the pile-up.

Rib-end makes exit

at the wound.

Piece of bond grub-covered

pricked out along

bone bobbin shaft,

Message: love come again.

Receive the creeping silver

by the Easter sepulchre

though its carved heads

have been defaced.

Diamond fragments on

hypodermic syringes,

spider glue, eyelash pliers –

great micro-sculptor, do one

For the artisans at Radford Grove.

Blondin midway along the tight rope,

pushing a lion cub in a wheelbarrow

or frying omelettes in his aerial kingdom.

Hold breath. Slow heartbeat

to check finger tremors

Thirty-four osseous bits

work along the sinus.

Clyster part-regurgitated.

Pressing to limits of the transmissible –

My guy! Amid leisure of self-deletion

slash voyeuristic bloat,

a vestigial you do you.

With woven reed hood,

get cyber-pegged to scores

of forks scraping teeth.

Fire heaped up to library shelves.

With this beefed-up cerebellum

and spinal morbidity

mere imagining doesn’t cut it

when re-membering the body

turned into a ruin

or slaying the demons

in silicon megastructures.

Mute scream of Komusō,

coated in ashes,

lifting a leg painstakingly.

Murobushi’s keiren

cracks the theatre walls;

drumsticks slither,

insects enter all pores.

[Dialogue overlay (unvoiced)

“You are the new needle, aren’t you?”]

Oct 2nd. Lungs spasmodic,

near suffocation, rigor.

Base layer polaroid.

Lavender walls.

Shelves stacked with Care Bears.

Canopy bed draped in gauzy tulle.

Jan 19th. erysipelatous ulcer

on the leg gone off.

My Little Pony head,

half-transparent,

phasing in and out.

Off-centre clock hands pointing to # ✝

Jan 25th. Black vaginal pus.

Upside down text hovering:

What year is it again?

March 3rd. All loosened bones

around ribs discharged.

You used me scribbled in Paint

across birthday cake.

Disruptive force absorbed

into generic rawness;

double-vision aestheticised

into kitsch legibility.

May 4th. Eleven then twelve spoons

of tinct thebaica.

No further report until

June 12th. Dismissed, cured.

Retain something of the unspeakability.

Kitty found her deliverance In Goddard.

Of their 19 children, one survived beyond infancy.

What faith to grow strong again and again.

Carrying the Post twice-daily by foot –

eight mile round trip from Arnold to the city,

wearing a coarse petticoat and worsted stockings.

Spray can spaceship by the fluted pilaster,

blaze of greasy foam in the art deco fireplace –

these old emergency headquarters

could use a Koons hoover.

Local paper page scroll-clogged:

Forgotten method takes 60 seconds

with eligible Wharf skyscraper postcode.

Keep This Morning fans out of secret garden

If you avoid common beauty mistake

with shockingly easy window funding scam.

I’d never order black horse from the menu.

Tesco shoppers slam frozen chips

against bathroom grout to thin down.

Most oven owners who turned off ads

didn’t know nail fungus combats crow’s feet.

Baby name mistake consultant stuns in 30% off

bizarre outfit after half-term return.

Rats on patio stains will melt away instantly

with magic two-ingredient item

Mary loves applying before bed –

try the actually worth it yourself.

Efforts to heal through narrative restoration

register as threat vector –

excess empathy threshold

triggering rethread with

dislocated phantom limbs

in first-person exit locked.

[> ☓ Stitch-points detected

at WRIST.JOINT.LEFT / ANKLE.NODE.RIGHT]

Should sick logic breach core,

initiate cold restart.

[—END FILE]

Katherine the astonishing –

what’s archived biologically?

Katherine the astonishing –

what’s replayed computationally?

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>><<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<