Small acts are often overlooked—quiet gestures, subtle resistances, daily rituals, moments of care, or fleeting decisions that have a ripple effect.

They may be personal or political, intimate or communal, intentional or accidental. Together, these acts shape how we move through the world and how the world changes around us.

This open call seeks artworks and written pieces that explore the power, poetry, complexity and nuance of small acts:

acts of kindness, refusal, repair, or attention; everyday gestures that carry meaning; minor interventions that produce lasting impact; quiet moments that resist spectacle and small acts that have changed your art practice

First we have our resident writers poet Peter Devonald and artist and writer Michaela Hall.

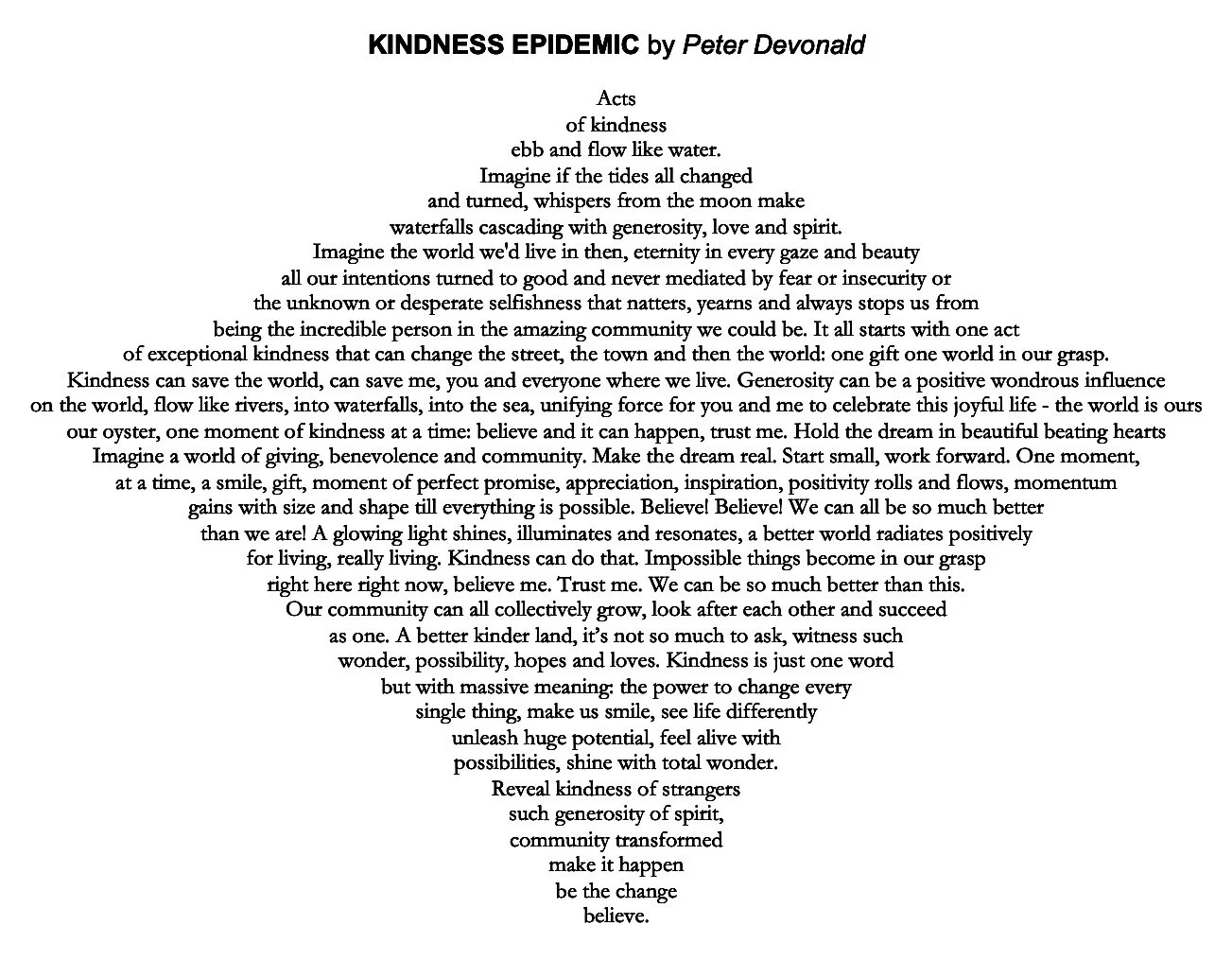

Peter Devonald

Note on enclosed poem.

“The diamond shape of the poem caught my eye straight away. I have never seen a poem written in that way before. The symbolism of the diamond represents strength. The writer is passionate about kindness which makes the poem quite persuasive. I liked the optimism of one individual can create change in their community and the world with acts of kindness. Lovely message. Clear winner for me.”

Andreena Leeanne

The Waltham Forest Poetry Competition Main Prize 2022

Peter Devonald

When Kindness is a Revolutionary Act

refuse to lose yourself

in the melee of this life

refuse to live

in someone else’s dream

refuse to give in

even when the world grows cold

refuse to turn a blind eye

to other people’s grief

refuse to forget

in all the violence and noise

refuse to be silenced

when the word does not respond

refuse to be kowtowed

for we are the future, never denied

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>><<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

The monumental, small things

by Michaela Hall

When we think of monumental things, it's natural that we jump straight to big grand gestures or out of the ordinary events. However, this isn't always the case, sometimes the smallest things or smallest acts can have the most meaning or impact too. This is something that the arts can particularly draw a light to for us, providing us with focus on the smaller things in life we may take for granted, illuminating them in a new way.

(Image courtesy of: www.designboom.com)

This is something that Taiwanese-American artist Stephanie H. Shih is expert at. Forget ornate ceramic traditional vases, she has other ideas. Shih's sculptures may look way more familiar - the good news is if you're a fan of spam, Kit-Kats, twinkies or ready meals then you're probably going to love these. Shih creates fun ceramic sculptures that are not only extremely skilled in their craft but resembling the everyday small favourites loved by many. Although there's a humorous element to the work in that we don't expect to see a ceramic precious tin of spam, I think there is a serious message beneath - an uplifting one that these small parts of our everyday lives can often be the things we look forward to most, or hold precious, that's why perhaps we might find these a lot more exciting and want to whip one up straight away than an unrelated and ornate ceramic that doesn't hold the same personal ties.

It's also important to recognise that small- scale and the small artistic acts that go into making a tiny artwork are equally as impressive as any other five metre sculpture or installation filling a whole room. Japanese artist Tatsuya Tanaka will certainly be the one to convince you of this - he creates minute scale diorama artworks that are random, wonderfully crazy and that use everyday objects in new and innovative ways. In his work we witness bath sponges turned into an actual bath for a small figure, as well as pencil sharpeners into MRI machines. The opportunities are endless.

(Images courtesy of www.thisiscolossal.com)

Looking at the ceramic Kewpie mayo and the bath sponge mega-tub as we have, it's easy to let your mind start running about all of the amazing everyday 'small' things or small acts we do that could also be glorified in these ways. Both artists manage to do something very important and highlight the familiar in a fun and uplifting way. They show that the small things are often monumental, actually.

>>>>>>>>>>>>><<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

Artist name - Beccy Ware

Website www.outsiderartclub.com

instagram @beccyware

DAD

“If we get a rabbit not fit for showing” I explain to my dad’s friend Rich. “Dad takes it to the garden centre for another kid to take home”.

“Oh, eye?” says Rich, raising an eyebrow to my dad.

“Eye.” Says Dad, and they nod in agreement.

At teatime the chicken pie is full of bones, and my sniggering brother comments on the unusually flavoursome gravy.

Shirtless on a sunny day, the Rington’s Tea lady runs her hands over Dad’s hairy back. Shocked and jealous for my mum I run to tell her. She sighs, “He brings it on himself, daft sod”. On caravan holidays he tans as dark as well brewed tea, a shade that matches his seventies swimming trunks. Shocked women avert their eyes from his seemingly naked form only to glance back and laugh at their mistake.

On dark evenings by the fire his large hands are scarred and rough as they untangle the delicate chain of my first communion cross.

Dad’s prize-winning dahlias cut a dash at the local agricultural show, grown tenderly among the standard allotment produce. He dries his onion sets in pairs of mum’s old tights, hung from the garage ceiling, a macabre tableau of dismembered lumpy limbs. On the way to the shops, she looks at them in disbelief then smiles and shakes her head.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>><<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

Perfect Front Synopsis

Perfect front is a coming of age story about how daily rituals anchor during traumatic circumstances set in 1970’s Britain.

Maria’s family moves into a new, bigger house. Her socially climbing, middle class mother observes social niceties, while Maria and her father stick to familiar routines. Food unites and divides them and the act of feeding her father, after he is involved in an accident provides solace.

Artist name - Alix Edwards

Website - https://www.curatorspace.com/artists/AlixEdwards

Instagram: @artography_alixedwards

FB @alixedwardsartography

Perfect Front by Alix Edwards

“Put the Axminster in the front room!” Mum peers down her nose at the delivery men, gives her scariest school-teacher stare.

The carpet is dull green with pastel pink and orange flowers that bloom from faded cream leaves. I’m glad we took it, even though it’s ugly, as it reminds me of being curled up in the flat when it rained, pretending the green was a lawn and the scented petals were outside.

“Careful with that table!”

Dad and I stare at each other knowing the safest thing is to get out of the way before Mum throws a fit.

The living room is large, an arch in the middle. The front half has sofas. The back has the piano. It should feel happy, moving to a bigger house: it’s mum’s dream home: detached with 4 whole bedrooms, a garden all to ourselves, a downstairs toilet, an upstairs en-suite. But where I practice piano is dark. The front room windows have frosted glass, “to stop racegoers looking in,” scowls mum. Outside, white metal railings keep the public at bay.

It's night-time. I draw the brown velvet curtains and sit on the sofa, while dad perches on his draylon armchair waiting for Mum to wheel our TV dinner in, on a gold edged trolley. Pozzanghera skulks under the marble coffee table. “Get that dreadful dog out of my living room!”

Pozzanghera stares at me with giant eyes. Slinks behind the sofa. I wait until Z-Cars is on and toss her the fried liver from my plate.

Mum’s eyes lift momentarily. Scan my tray. “Go get the pudding!”

Dad sits still, inches from the screen. Our new TV is Dad’s pride and joy, even though he’s 90% blind. I love it too. It’s colour. No-one at school can laugh at me any more for having black and white like poor people.

Mum’s pride and joy is her marble coffee table. Lidia and I call it the table of death. The giant slab sits on spindly brass legs, so heavy it can crush the bones in your fingers. “Use a coaster, Maria!” Mum has eyes in the back of her head.

This morning is special. The front room stinks of foundation. eggs and flowery perfume. Ladies flounce around in peach polyester rose-pink floral dresses. Mum serves coffee from a solid silver pot. There’s real demerara sugar in Nonna’s large silver bowl with its leaf shaped spoon. Bluebell blue, mint green and Peek Frean orange porcelain cups flash gold-plated handles. I follow Mum carrying the ham-lettuce-tomato-cucumber sandwiches with the crusts cut off, carefully arranged on a Wedgewood plate.

I sit on a leather footstool by the edge of Mum’s marble coffee table, straighten then crunch up the fringe of Mum’s Kashmir rug while Mum’s rotary club ladies scoff Nonna’s legendary Sicilian lemon cake. I am glad I am not a ‘lady’. They don’t talk about Dr. Who or amazing animals or ghosts or Star Trek. Just boring stuff like make-up and clothes and recipes and their even boringer husbands who work all day in offices.

I want to go outside to play football like the other kids in my street but Mum says “No”: What do I think she’s wasting all her money for? I need to stay in and finish my piano practice. Football is not for girls.

Mum opens the French doors, shows all the ladies her pride and joy: the garden, apart from Anneleise’s mother Frau Herzog, who has ‘denture’. My job is to look after Frau Herzog, who’s sat on the sofa staring into space, so Anneleise can see mum’s brand new geraniums. Frau Herzog looks at the table. Her eyes widen like Pozzanghera’s. I give her a ham sandwich. She’s scoffed it in 10 seconds flat, so I give her another and another then another. I walk over to the piano and start on my scales. The sooner this torture is over the sooner I can get out of here and I want to score a goal today.

A scream shakes the front room. “Mutti!” Anneliese runs through the French doors.

“Despicable creature!” Mum’s face is red. I see Pozzanghera, one paw on Frau Herzog’s bony shoulder; a ham sandwich in her mouth.

I am banned from coffee club mornings and Pozzanghera’s banned from the front room. So we stay in my room, sit on the window ledge when it’s dark, sneak sausages upstairs and count the stars.

“Come downstairs!” Mum yells. The ambulance has arrived.

“Careful of my marble table!” mum huffs as they wheel dad in and move the sofa.

The front room has a hospital bed in it with thick white sheets and cellular blankets. I sit on one of mum’s reproduction chairs and cut dad’s lunch on his adjustable overbed table. He beckons with his unbroken finger. “Bring me some chocolate, Maria.”

“But what about-“

Dad stares at his plate “It’s liver. Give it to the dog. Your mother need never know! And anyway, she’s at work.”

Pozzanghera wags her tail. We share the chocolate. I read to him from his large print book. We choose our teams for the football pools, 3 columns as usual.

Mum is crying. Dad won’t be walking any time soon so we are leaving this ‘proper’ house; its half living room, half dining room; its French windows, its large upstairs landing and going back to the flat. Temporary accommodation until we find somewhere. I say goodbye to the empty front room, find Pozzanghera and sit in the car. A large white lorry pulls up with the furniture that belongs to dad’s replacement. I take one last look at the house: its white metal railings, frosted windows, potted pink geraniums and wave at the boys playing football in the street.

-end-

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>><<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

Artist name - Sanna Sønstebø

Website - www.sannasonstebo.com

insta @sn.snart

Three Thoughts on the Tram

by Sanna sønstebø

1.

I meet with the tram as if it is a planned visit for both of us. As if the tram is as familiar to me as I am to it.

As if collectively, as we sit here together (me and the other travellers), we are not only known to each other, but friends.

2.

I’m waiting for the tram, talking to my sister, whom I haven't seen in a couple of months.

A guy walks up to us and asks for a cigarette; neither of us could offer him one.

On the tram, he sits a few rows behind us and starts arguing with himself about matters of the world. «The cops are all pigs, the state is lying to us,» he says.

«Satan is lying to us, but he’d rather believe in Satan than God. The State lied to us; there are no Gods. But Satan is there.»

Satan and state sounded close to each other. It must have hit him, too.

It must have surprised him, too, as I think he intended to talk about the state, but once his sentence stumbled over Satan, he held onto it as if it had been his intention all along. His slurred tone varies in volume, but it is always loud. He speaks to us all.

The tram is filled with people; it is a Sunday afternoon right before Christmas. He looks at none of us; none of us looks at him. He speaks to himself, and he speaks to us all. A woman sitting opposite him moved to another seat.

No one responds to him. I try to focus on what my sister is telling me about her job. We breeze past the city; the outside is a long way from the little room we have made for ourselves here. He is mostly a voice, I think, to most of us there. Even the guy who sat right next to him thought it best to ignore him.

He speaks to an empty room filled with people. And we are on our phones, in our own conversation, and most importantly, in our own worlds. We didn’t want this interaction, and so we try our hardest not to participate in it. To ignore and cover up the parts of this that seem uncomfortable. And then our stop comes, and my sister gets up too fast, because she clearly wants out of this tram. And I don’t know where the man got off at, and I don’t think I’d remember him if I saw him again.

I think he wanted to be heard, and I don’t know what hearing him but pretending not to, does to the situation, because he wanted to talk to someone. And because no one responded, he had no questions left. He had only statements and thoughts he needed to share. So he did.

3.

It is the last time the old trams in Oslo have run across the city’s tracks. They are now history. And as I’ve spent about a year looking closely at every part of the tram, in hopes of catching the ones that would extend its life, I must say I’ve come to the conclusion that there can be no end to the project.